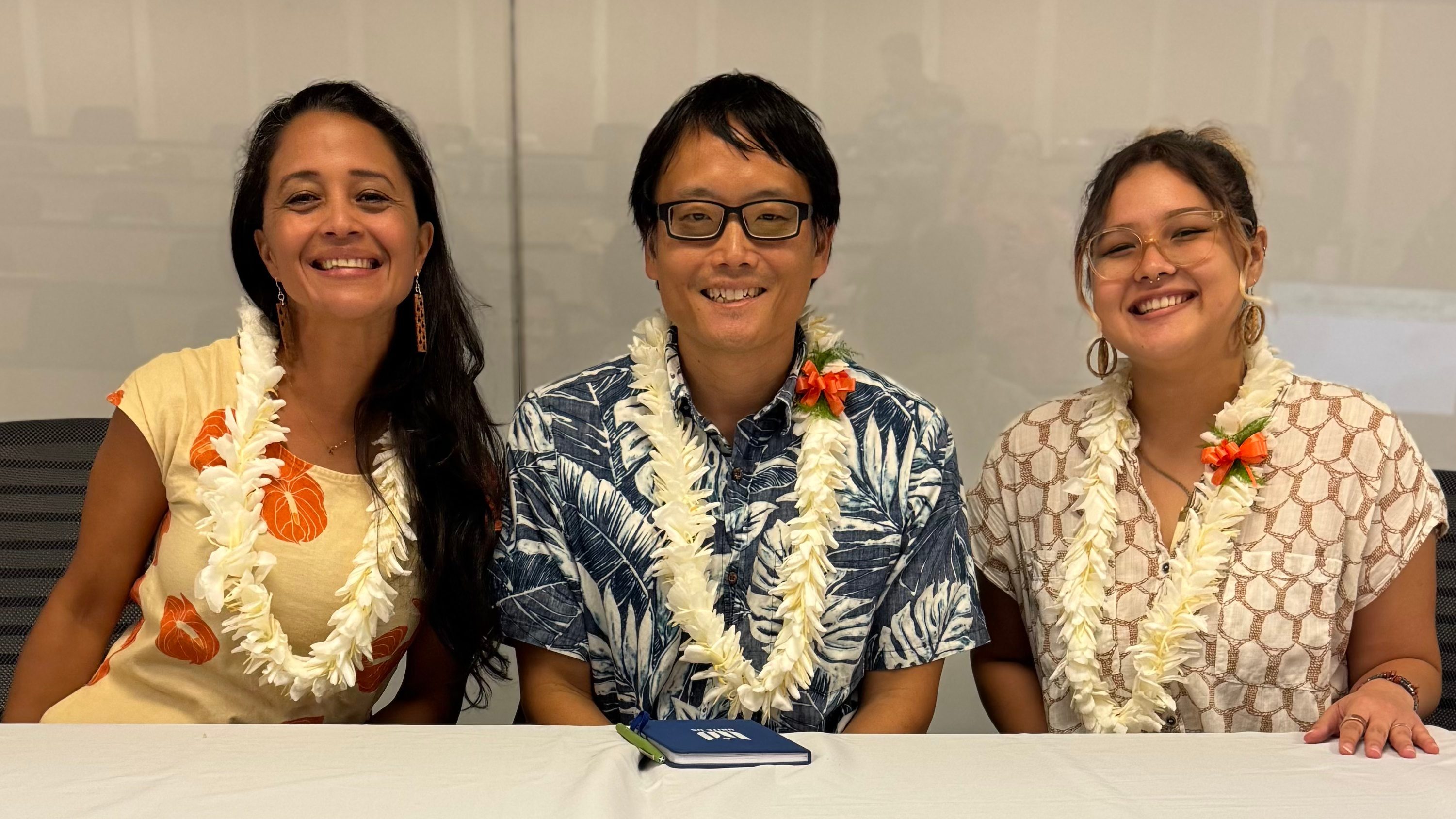

On October 2, 2025, 2L Heona Ayau-Odom ʻ27 moderated the Maoli Thursday panel Duty to Aloha ʻĀina: Examining Military Leases on Hawaiʻi’s Public Land Trust ʻĀina. The panel brought together Wayne Tanaka ʻ09, Director of Sierra Club of Hawaiʻi, and Ashley Obrey ʻ09, Senior Staff Attorney at Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, for an in-depth conversation on ongoing military lease negotiations, accountability, and restorative justice.

The discussion began by exploring the history, current realities, and legal dimensions of military leases over Hawaiʻi’s public land trust ʻāina. The lands form part of the public land trust established at statehood under the Admission Act, enacted by Congress in 1959. Commonly referred to as “ceded lands,” they were originally taken from the Hawaiian Kingdom and later transferred to the state to be held in trust for five purposes, including the betterment of Native Hawaiians and the general public.

Under Hawaiʻi’s Constitution and trust law, the state serves as trustee and bears fiduciary duties to protect, preserve, and productively manage these lands. In Ching v. Case (2019), the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court unanimously held that the state breached these duties by failing to monitor military compliance, resulting in unexploded ordnance and hazardous debris left across sacred ʻāina. The Court reaffirmed that the state’s constitutional trust duties—grounded in the principles of aloha ʻāina and mālama ʻāina—require active stewardship and protection of these lands.

The military’s 65-year leases—covering approximately 23,000 acres at Pōhakuloa for just $1—are set to expire in 2029. The area encompasses rare subalpine tropical dryland ecosystems and lands designated for conservation. Under the existing leases, the military is required to remove training debris and restore the lands after use. As the expiration date nears, the military is seeking to renew its leases. Decades of non-compliance, however, raise serious concerns about whether renewal would align with the state’s trust obligations.

As trustee, Hawaiʻi’s Department of Land and Natural Resources is responsible for ensuring that the conditions of these leases are fulfilled and that public trust lands are not left in disrepair. Any new or renewed lease will trigger Hawaiʻi’s environmental review process, requiring a final environmental impact statement (“EIS”) before the Board of Land and Natural Resources may consider approval. Previous EIS submissions for Pōhakuloa were rejected in May 2025, underscoring the rigorous legal and procedural standards that must be met.

Governor Josh Green has increasingly framed the lease-renewal process with the U.S. Army as a national security matter, claiming that federal officials have suggested eminent domain could be invoked if new lease terms are not reached. Tanaka and Obrey noted, however, that any discussion of a land exchange must still comply with the Admission Act, which requires surplus federal lands to be returned to the State of Hawaiʻi. They further explained that these lands are part of the public land trust and carry fiduciary obligations to Native Hawaiian beneficiaries—they are not discretionary assets to be negotiated away. The panel concluded by emphasizing that decisions about the future of public land trust ʻāina must reflect their legal, cultural, and relational significance, rather than be driven solely by military priorities. Ultimately, the future of Hawaiʻi’s public trust lands rests not only on legal outcomes, but on the growing momentum of broad-based community engagement guiding the decisions ahead.